In the last lesson we reviewed the basic blues progression along with using the 9th an 13th chords (Click Here for Blues Lesson 1).

In this lesson we are going to look at more extended chords and altered chords that can be played in place of the dominant 7th chords. We will also see that the basic 1-4-5 progression itself can be altered.

Below is an example of a blues progression with some examples of altering the basic 1-4-5 structure.

| G13 | C9 | G13 | Dm7 G7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| C9 | C9 C7b9 | G13 Am7 | Bm7 Bbm7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| Am7 | D13 D9 | G13 E9 | Am7 D9 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

Let’s look at the measures in the example above. The first 3 measures are pretty much the same as the examples we saw in the last lesson. In the 4th measure we are going to play a Dm7 to G7. Why? The Dm7 to G7 acts as a 2-5 progression that resolves itself to the C (C9 in this case) chord. This would be the 1 chord in the 2-5-1 progression, ie. Dm7-G7-C(9).

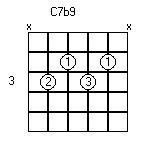

The 5th measure is the same as in the previous lesson, but the 6th measure has C9 for the first 2 beats and then a C7b9 (shown in the figure above) for the last 2 beats. This adds some variety to the sound.

Measures 7, 8, 9 and 10 demonstrate a vehicle that resolves into the 5 chord of the basic 1-4-5 (in this case the D9 chord). How did we get there? The G13 to Am7 starts the motion towards the final destination of the D9 chord. The Bm7 to Bbm7 continues the motion and gets you to the Am7 chord. Now the Am7 chord and D9 chord combination is another 2-5 progression resolving to the 1 chord, G13 in this case.

Measures 11 and 12 provide an example of an alternate ending for a blues progression. It is basically a 1-6-2-5 progression with a dominant 7 played for the 6th chord as opposed to the usual minor chord that is typically played for that progression.

Let’s look at more variations in the example below.

| G13 | C9 | G13 | Dm7 G7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| C9 | C9 C7b9 | G13 Gb13 | F13 E7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| Am7 | D13 D9 | Bm7 E9 | Am7 D9 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

In the above example note the descending progression in the 7th and 8th measures from G13 down to E7. Also note the ending change in measures 11 and 12 that use 2-5 progressions from Bm7 to E9 an Am7 to D9 resolving down to the 1 chord (G13).

Let’s look at another example with a different ending.

| G13 | C9 | G13 | Dm7 G7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| C9 | C9 C7b9 | G13 Gb13 | F13 E7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| Am7 | D13 D9 | B7 E9 | A7 D9 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

The only difference in the example above is that we have substituted B7 and an A7 for the Bm7 and Am7 in measures 11 and 12. Not a major difference but it adds some variety to the sound.

Now we are going to build on that ending and modify it a bit. See the example below.

| G13 | C9 | G13 | Dm7 G7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| C9 | C9 C7b9 | G13 Gb13 | F13 E7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| Am7 | G#7b5 | G13 Bb13 | A13 G#13 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

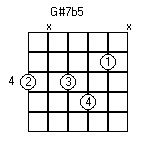

The modifications start occuring in measure 10, where the G#7b5 chord is used in place of the normal 5 chord. How can we do this? We are using what is called a “tri-tone” substitution for the 5 chord, which is a very common and popular thing to do with jazz and progressive blues. The basic rule of thumb is to play the dominant 7th chord that is 3 whole tones up from the normal dominant 7th 5 chord. So in our example the normal 5 chord is D7. Counting 3 whole tones up from there would be E – F# – G#. So we could use G#7. I chose to use a G#7b5 because I prefer that sound and the b5 note (which is a D in this case) helps to resolve down to the G13 because the D note is the 5th note in the G13 chord. Why does the tri-tone work? It provides a chromatically descending bass line from the 2 chord down to the 1 chord, in this case the bass notes are A – G# – G.

In measures 11 and 12 we see more examples of using tri-tone substitutions. The Bb13 is used as a tri-tone substitution for the E9 and the G#13 is used as a tri-tone substitute for the D9.

Let’s compare the most basic 1-4-5 blues progression that we learned in the first lessons with the last example.

| G7 | C7 | G7 | G7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| C7 | C7 | G7 | G7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| D7 | C7 | G7 | D7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| G13 | C9 | G13 | Dm7 G7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| C9 | C9 C7b9 | G13 Gb13 | F13 E7 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| Am7 | G#7b5 | G13 Bb13 | A13 G#13 |

| / / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

Quite a difference between the 2. You can alter the progression even further if you want as other musicians have in the past. Study blues progressions by famous musicians like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis and you will find blues progressions even more altered than what we have covered in this lesson.

That’s it for this lesson.

Domenick Ginex is a guitarist living in Tampa, Florida. He has played in several groups in the Tampa Bay area for over 25 years.

Related Article:

Domenick Ginex’s lesson on Blues Soloing